Reducing Friction is Not Enough

Being lazy should not require so much effort

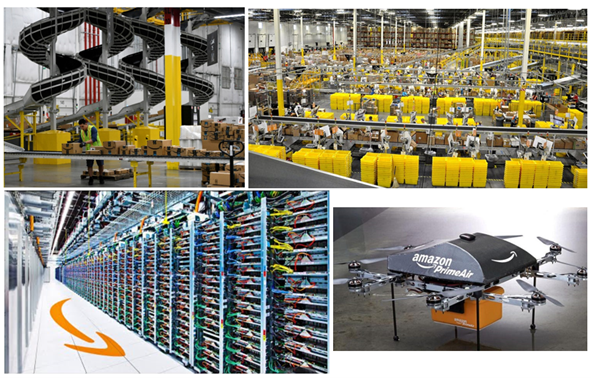

Over the past quarter century, Amazon has built arguably the most impressive fulfillment, distribution, and logistics system ever created- enabling hundreds of millions to receive nearly any type of product within two days. To accomplish this, the company has developed bleeding edge robotics, enormously complicated warehouses, massive cloud computing networks, and countless other technologies that would have been considered fantastical only a few years ago.

One of Amazon’s greatest innovations, however, is something so commonplace and banal that we easily forget how important it was to the growth of online shopping: 1-Click Ordering. Instead of entering personal contact information, a shipping address, a billing address, credit card numbers and expiry dates for every single online purchase, a customer could simply store this data and click “buy now.” 1-Click Ordering was so successful that Amazon not only patented it, but actually managed to license the product to Apple in September, 2000. This feature was characteristic of an integral strategy within Amazon’s broader customer obsession approach: reducing friction. If transacting is effortless, shoppers will make more frequent purchases, driving sales and increasing customer loyalty.

Reducing friction is a well-documented strategy and a central tenet of many businesses. While it might make an activity more seamless, the core activity is unchanged: the Amazon customer is still paying the same price for the same roll of paper towels. Reducing friction is certainly more than lipstick on a pig, but it has its limitations.

Consider Netflix and Peloton. Netflix’s suggestion algorithm, auto play next episode, and countless other subtle UX nudges have made sitting around, watching endless television easier than ever- something people are naturally predisposed to doing. Peloton has similarly streamlined a popular activity- attracting users with engaging and motivating group classes-, but for vigorous, inherently uncomfortable exercise. Netflix has risen 17% in 2021 to a market cap of around $270B with nearly 214M paid subscriptions (and who knows how many users per login). Peloton, after a tremendous period of stay-at-home, stimulus check, and other COVID related tailwinds, has fallen 75% YTD to a $12B value (from an undeniably rich $53B or ~29x sales in December 2020) with 2.5M subscribers and a rising churn rate. Put as a clumsy heuristic: spare change is found in (TV-facing) couches while bikes are a reliable money pit.

These are cherry-picked figures and comparing the two companies is a stretch, but the broader point stands: firms that reduce friction to facilitate desirable or “default” human tendencies have larger TAMs, require less in the way of expensive marketing to entice customers, and are more enduring with less fad-risk. “People are lazy and will continue to be” is a solid foundation for any investment thesis.

Extending the laziness observation further, instead of choosing the hard route of reducing friction for an unpleasant activity, bypass the activity entirely and retain the upside. With the Peloton example, people primarily use the product for the physiological gains, but a non-trivial portion of the appeal is the status, association with a “healthy” activity, and perceived feeling of accomplishment. Think how great a business would be if it could replicate the non-physical benefits without the pain and hassle of a spin class? Lululemon clothing confers a degree of stylish status, projects a health-conscious mindset, and may even have positive psychological effects not too dissimilar from completing a workout. Though a stretch, companies that sell minimal effort, non-vice (i.e., no substances) products that can effectuate good feelings without the previously required exertion have significant value under the laziness hypothesis.

Then again, maybe the problem all along is that 1-Click is frankly too much friction:

Entertaining read. Glad to have stumbled upon this.